He opens the door with a halfway-buttoned shirt, halfway-shaved face, leather loafers, and a slightly frazzled grin, but welcomes me in right away into exactly what one would expect Art Garfunkel’s apartment to look like. Stacks of books, demos, and records find homes beneath spindly-legged furniture. A large canvas decorated in colored signatures reads love from West Choir! and we heart Art.

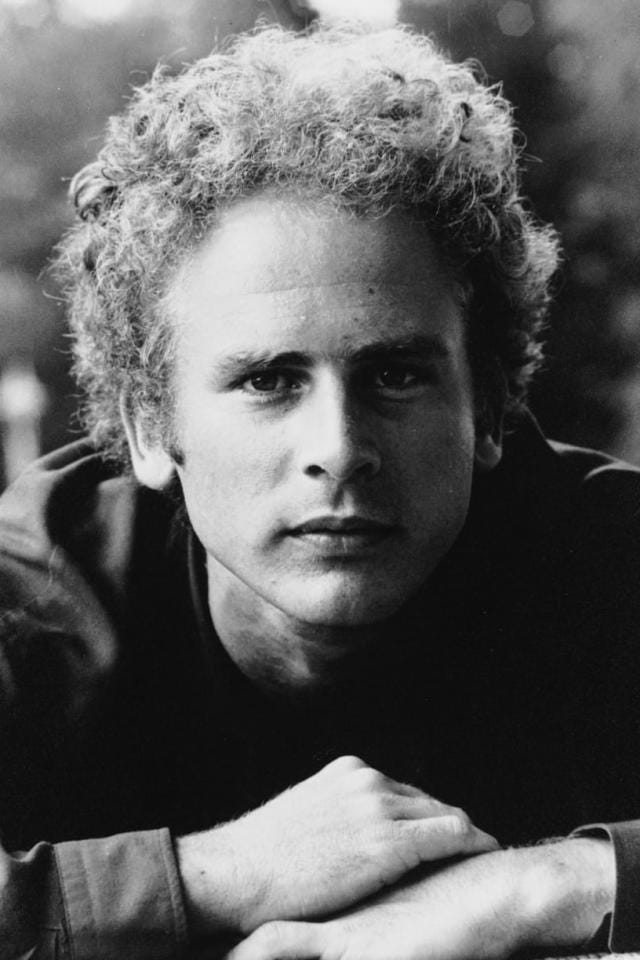

Quipping about a recent trip to Switzerland, Art Garfunkel, 77, makes only tiny, pointed movements paired with long and superfluous monologue. The wisps of his curls are visible on either side of his head, poking through the lenses of thick glasses. Looking out the window, he sighs and says, “I shouldn’t have come back to New York. I don’t want to see anyone.” But in Zurich, a dream world that lights up Garfunkel’s face at the vision of rolling hills and mountain peaks, the Queens native may find a new home. His oldest son Arthur Jr. (“He’s not overplayed with life,” Garfunkel said) had found him a lovely house. It sounds as though all he wants is to not feel so out of place.

Art Garfunkel, once half of an Everly Brothers-emulating duo called Tom and Jerry, is widely considered to have retreated from fame. He is certainly less accessible than his performing counterpart Paul Simon, and he makes no secret about his desire for total privacy and anonymity. A sixth-grade math packet lies on his kitchen table, a reminder that he is still simply a father with a young son working through oddly solved math equations over a homework table.

By the time Garfunkel was in high school, he had already been on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand with Simon. As friends and as performers they became inseparable; the harmony to each other’s angelic melody, Simon and Garfunkel would go on to create some of the most definitive Americana samples of the century, defining decades of social and cultural change.

“We fall into things,” Art says in explanation of his music. Yet little about him is that simple. “We have a way of denying ourselves…” he trails off. “Everyone is wildly in love with being alive. But on the inside.” Garfunkel laments that neither he nor I can ever converse and truly understand each other, and that nothing he wants to say will translate into print. I assure him that it will.

For Simon and Garfunkel, things have never been so simple. Even after hiatuses, the two inevitably found each other again. In 2004, the pair held a free concert at the Colosseum in Rome. Over 600,000 attended. Garfunkel calls it “luck” that his music has reached so many years, that high school choirs still sing “Feelin’ Groovy” and “Scarborough Fair.”

“If you eat something that tastes delicious, that’s great,” he says. His answers are commonly analogies. “If it stays delicious for 45 years, that’s just an extra treat.” He pauses. “That was good. I’d write that down, if I were you.”

His drug of choice is caffeine, and he especially loves Snapple (lemon or peach). After some reflection, he decides that caffeine may not be such a bad addiction to have. Garfunkel ditched his Marlboros years ago, but the damage on his vocal cords was done. He lost his voice in 2010, canceled a tour with Simon, and spent the subsequent four years yelling into empty theaters trying to force his range to resurface. Before reporting to the Rolling Stone that his voice was officially back, Garfunkel spent four years without access to his primary form of artful expression. He turned, instead, to writing, something that he had never given the opportunity to fully root and blossom, though he traveled the world in his youth with a notebook in his back pocket. These decades-old writings became his unconventional autobiography, What Is It All but Luminous: Notes from an Underground Man. It is full of musings and things that don’t feel so far-fetched for Garfunkel to have penned. A personal favorite is “you can’t discover fuchsia twice” – page eight.

“The thing that I’ve been thinking about is, where does it take me?” Garfunkel says of his writing process. “Where does the rhythm take me? What does it demand?” What results are micropoems, which he calls “bits.” He now integrates his poems into his live shows, which admittedly excites him. Since 1968 on the set of the film Catch-22, Garfunkel has kept a detailed, perfectly handwritten list of his books, with dots by the ones he’s found especially thought-provoking. “Paul used to say, ‘My friend Artie, the human typewriter!’” Garfunkel smiled. 1,271 books lived on the list at the time of our chat. Some of his dotted favorites included Saint Augustine’s Confessions, Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, Jacques Barzun’s From Dawn to Decadence, and most recently, How to Grow Old by Marcus Tullius Cicero.

He recites a poem inspired by Jacques Barzun, looking up frequently to ensure that his audience is paying rapt attention. “Nothing is profound,” he reminds me. Yet this does not seem like something he actually believes; it sounds like a joke on the tip of his tongue, like he is just holding back a laugh at his own cynicism. When he’s finished with his own book, he shows me another: an illustrated children’s book titled When Paul Met Artie by Gregory Neri. On the inside cover, Garfunkel had written a message to his youngest son Beau with all his love.

We avoid the topic of Paul Simon for the most part, which was very much my plan. We gripe about the drama of it all – the 2015 Telegraph article claiming Garfunkel “created a monster” out of Paul Simon, which is very much not what he said – and roll our eyes at the need for media to find something juicy enough to publish. It reminded me of something that Garfunkel had said in an older interview. It was something that George Harrison had said to him at a party: “My Paul to me is what your Paul is to you.” When I ask him about this, he tells me I’ve done my research, smiles, and says nothing more.

What could possibly be next for a man who’s done everything? “I haven’t done everything, but what a great thought,” he says. “I don’t know how to record now. I’m afraid I’ll get lost. Do I make a YouTube? Where do I even begin?” He asks it less with curiosity and more with wistfulness. “When I made Bridge Over Troubled Water, I made it for people. But I also made it for art’s sake, capital A.” L’art pour l’art. How fitting.

Simon had announced his farewell tour, and some have wondered aloud whether Garfunkel might reunite with his old friend for one last show in Central Park. Maybe then we could turn the time back to 1981, recapture some of that nostalgic wonder in the misty rain of what feels like a different city. Something about those emotional connections with celebrities, especially music, makes us claim ownership over those that have carried us through the phases of our lives. As if somehow, moonlit in the park again with a half million people, Paul and Artie will emerge just the same. This is the way we escape reality. Nothing has to change at all – even us. But that rose-colored memory, the façade of perfect harmony, was cracking deeply underneath the surface even then.

On the 141st page of Garfunkel’s autobiography, he writes, “To Paul, from Art: We’re out under the stars now, the harbor we came from is gone from view.” Amidst the books, tapes, demos, papers, photographs of his wife and children, hotel room notepad scribbles and vase upon vase of freshly cut tulips, all Garfunkel wants is exactly what he seeks. “To be whole, balanced, full – that is all a woman or a man wants,” he said. And that is all he is – a singer, writer, father, perceiving his past as if he is an ocean liner on the horizon in a vast sea, or like a list of memories dotted perfectly.

When we meet our heroes, we must learn to let them live in harmony with our pedestalled love in an overall acknowledgement that they are human, too. Art Garfunkel shuffles around his apartment and I forget for a moment who he is – what he represents. I then discover Art twice, in a way; this favorite voice in my ear becomes a writer on a page, a poem spoken crisply and purposefully into a crowd, a delicate frame in a soft chair reading like the sage I always imagined he would be. A man that in his fragile frame still embodies generations of art, of transformation, of love. But still only just a man. He sings scat and whispers about old friends.